When a person’s heart stops beating, the immediate use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can mean the difference between life and death. CPR is a life-saving skill that ensures blood continues to circulate, delivering oxygen to vital organs, particularly the brain, until emergency medical professionals arrive. Despite its simplicity, the application of CPR is hindered by social perceptions and biases that contribute to disparities in its administration, especially concerning gender.

Recent findings highlight an alarming trend: bystanders exhibit a significant bias toward performing CPR on men rather than women. A study conducted in Australia between 2017 and 2019 analyzed over 4,000 cases of cardiac arrest and discovered that the likelihood of receiving CPR was markedly lower for women—65% compared to 74% for men. This disparity raises critical questions about the underlying reasons for this trend and indicates a need for deeper exploration into the sociocultural dynamics at play.

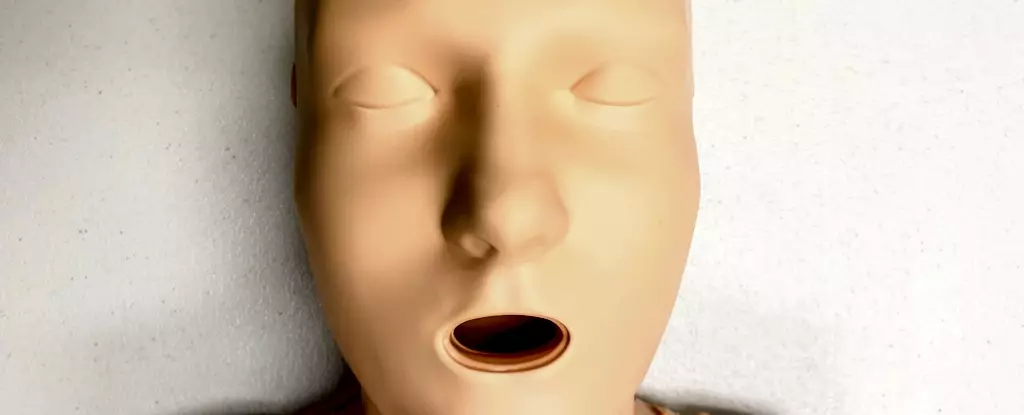

One of the focal points in investigating this issue is the type of CPR training provided. Predominantly, CPR training utilizes anatomical manikins that rarely represent the female body accurately. The majority—an astounding 95% of these training devices—are flat-chested, which could contribute to the hesitance among bystanders when it comes to assisting women in distress. While CPR techniques remain anatomically consistent regardless of breast presence, the societal implications tied to the absence of breast-narrative cues during training could skew bystander perception and willingness to act.

This situation is compounded by the increasing prevalence of cardiovascular diseases among women, who are often underrepresented in clinical studies. Given that heart disease remains the leading cause of death among women globally, this gender gap in training and recognition of symptoms can lead to delayed responses in an emergency, further jeopardizing women’s health outcomes.

Research has indicated that the reluctance to perform CPR on women can stem from various psychological barriers. Bystanders may fear being misinterpreted as engaging in inappropriate behavior, especially when physical contact is necessary. Additionally, there is a pervasive notion that women may be more fragile, which can lead to reluctance to intervene. This hesitancy can severely impact timely rescue attempts, particularly in emergencies where every second counts.

Studies have also shown that during simulated rescue scenarios, CPR participants were less inclined to undress a woman to perform life-saving procedures. This hesitation exists even when the intervention is critical—the absence of immediate action in these scenarios reflects a larger societal fear and misunderstanding about contact and consent during emergencies.

To address these disparities, it is crucial to broaden the representation in CPR training manikins. In a survey of the current market, researchers found that out of 20 available CPR manikins, only five were marketed as “female,” and merely one of those had breasts. This lack of diversity in training equipment speaks volumes about the implicit biases that pervade medical training. Developing CPR manikins of various body shapes, sizes, and gender identities is essential in moving toward equitable healthcare training.

Making training materials inclusive can serve multiple purposes. Firstly, it helps normalise the act of providing CPR to all body types, reducing the associated stigma. Secondly, it empowers individuals to respond confidently in life-threatening situations, irrespective of the victim’s gender.

The issue of non-intervention in female cardiac arrest cases is multifaceted and deeply rooted in cultural misconceptions. Addressing these barriers requires comprehensive education that emphasizes the symptoms of cardiac arrest across genders and reinforces the importance of timely intervention. Training programs should focus on encouraging individuals to recognize the signs of cardiac emergencies and take immediate action without hesitation, regardless of the victim’s gender.

Additionally, public health campaigns should aim to raise awareness about the equal risks women face regarding heart conditions and the critical need for women to receive CPR just as promptly as men. By reinforcing the idea that immediate intervention, irrespective of gender, is paramount, society can work toward eradicating the biases that currently inhibit life-saving measures.

The life-or-death nature of CPR necessitates urgent and transformative measures in training and education to ensure gender equity in emergency response. By diversifying CPR training materials and emphasizing education about heart health and emergencies, we can equip bystanders to act decisively, thereby improving survival rates for everyone, particularly women. Society must work together to break down the cultural barriers surrounding CPR, fostering an environment where all lives are valued equally, ultimately enhancing community resilience in the face of cardiac emergencies.

Leave a Reply