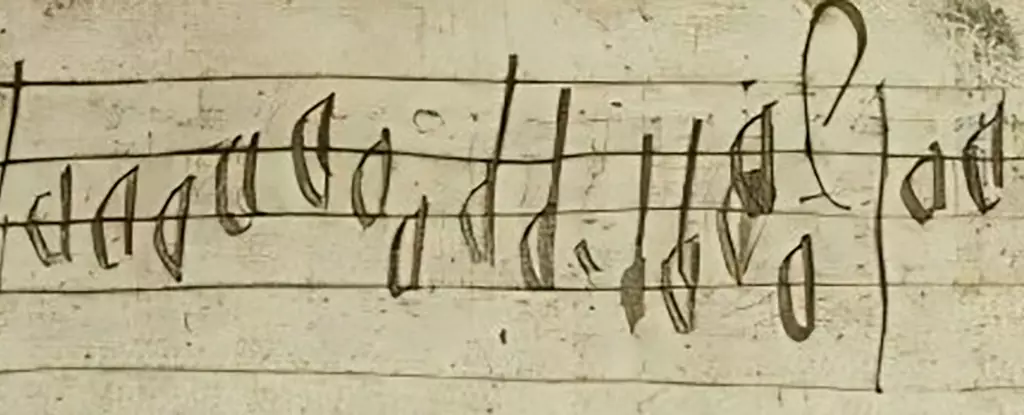

Music has a unique ability to evoke memories, transporting individuals to different times and places through sound. Recent investigations by researchers from KU Leuven and the University of Edinburgh have opened a window to the auditory landscape of 16th-century Scotland, revealing a snippet of music that had remained dormant for centuries. This fragment, consisting of just 55 notes, was discovered in an unexpected location: the margins of the Aberdeen Breviary, an important liturgical book printed in 1510. While it may not be a bestseller, this tome holds significance as the first full-length book printed in Scotland, illuminating the historical context from which this musical piece emerged.

The fragment’s discovery provides a rare insight into a pre-Reformation Scotland, a period previously thought to be largely devoid of surviving musical works. Instead, this established a potential narrative of rich liturgical traditions that had been obscured by the Reformation. Scholars are particularly intrigued by the lack of musical records from this region, making this 55-note piece a compelling find for researchers dedicated to understanding the cultural frameworks of Scotland during this transformative era.

The fragment has been associated with “Cultor Dei, memento,” a Christian chant performed in Anglican churches during Lent, suggesting a possible continuity of traditions across centuries. Despite the absence of attribution or titling, this single line of music allows historians and musicologists to piece together a larger tapestry of Scotland’s musical heritage. The fragment follows polyphonic composition rules—the simultaneous intertwining of melodies—suggesting a sophisticated level of musicality that challenges conventional beliefs about musical development in Scotland before the Protestant Reformation.

David Coney, a musicologist involved in the research, describes the impact of the find: “From just one line of music scrawled on a blank page, we can once again hear a hymn that lay silent for nearly five centuries.” Coney’s reflections point toward the transformative power of musical archaeology, both in resurrecting lost sounds and in recontextualizing the role of music in historical narratives. This makes the research not merely about notes on a page but about restoring a sense of cultural identity that had diminished over time.

James Cook, another musicologist participating in the study, expresses surprise at the findings, commenting on the persistent belief that Scotland was barren of sacred musical culture prior to the Reformation. The study underscores the existence of a vibrant musical tradition within Scotland’s churches and cathedrals—an aspect of history that had previously been underexamined. “Our work demonstrates that despite the upheavals of the Reformation… there was a strong tradition of high-quality music-making in Scotland, just as anywhere else in Europe,” says Cook. This revelation invites scholars to rethink preconceived assumptions about the country’s musical evolution.

The investigation into the ownership history of the Aberdeen Breviary provides additional layers of context. Links to figures such as Aberdeen Cathedral and St Mary’s Chapel suggest not just academic connections, but flesh out the everyday reality of religious and musical life during this era. Understanding who may have interacted with the notation and where it might have been sung enriches the narrative surrounding this period, maintaining a connection to the everyday lives of those who lived and worshipped through song.

The excitement surrounding this finding does not end with the notation itself; it raises the tantalizing possibility of more undiscovered musical pieces hidden in the margins and blank pages of similar texts. Paul Newton-Jackson of KU Leuven emphasizes the potential treasure trove of resources that remain unexplored. “It may well be that further discoveries, musical or otherwise, still lie in wait in the blank pages and margins of other sixteenth-century printed books,” he remarks. This highlights an avenue for ongoing research that seeks to illuminate an entire world of forgotten melodies and their cultural significance.

Through the careful analysis of this 55-note fragment, researchers have initiated a reexamination of Scottish musical history, shedding light on a time and place previously shrouded in silence. By piecing together scattered notations and engaging with the broader historical context, these findings advocate for the importance of music as a vital thread in the fabric of cultural identity. Far from a barren landscape, 16th-century Scotland reveals itself as a rich tapestry of sonic narratives waiting to be uncovered, a call to remember the chords of history that have the potential to resonate once more.

Leave a Reply